In a groundbreaking fusion of technology and conservation, augmented reality (AR) is breathing new life into creatures long lost to extinction. Museums and research institutions worldwide are pioneering immersive experiences that allow visitors to interact with digitally resurrected species—from the majestic woolly mammoth to the enigmatic dodo bird. This innovative approach isn't merely about spectacle; it represents a profound shift in how humanity engages with ecological history and biodiversity loss.

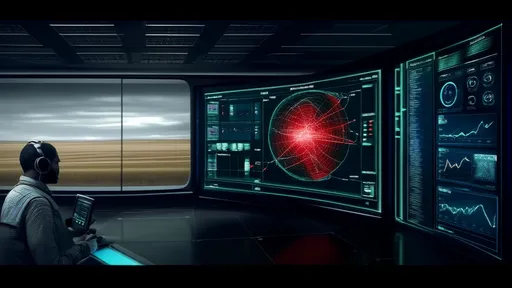

The concept of "virtual species revival" leverages photorealistic 3D modeling, spatial computing, and behavioral algorithms to recreate extinct animals with startling accuracy. At London's Natural History Museum, visitors wearing AR headsets can watch a Thylacine (Tasmanian tiger) stalk through the museum's corridors, its striped hindquarters twitching as it sniffs the air. Meanwhile, the Smithsonian's "Ghosts of Evolution" exhibit uses smartphone apps to make Passenger Pigeons erupt from archival display cases in swirling flocks that visitors can walk through.

What sets these experiences apart from traditional dioramas or documentaries is their dynamic responsiveness. The AR creatures don't follow predetermined scripts—they react to human presence, environmental changes, and even each other. A team at Kyoto University programmed their digital Japanese River Otters (declared extinct in 2012) to exhibit curiosity toward children while avoiding adults, mirroring historical behavioral accounts. This layer of artificial intelligence fosters emotional connections that static displays cannot achieve.

Behind the magic lies meticulous scientific collaboration. Paleontologists, geneticists, and indigenous knowledge keepers work alongside AR developers to ensure anatomical and behavioral authenticity. For the Great Auk project, researchers cross-referenced 19th-century taxidermy specimens with Inuit oral histories about the bird's swimming patterns. The result? A clumsy walk on land (as described by sailors) that transforms into graceful underwater propulsion when viewed near a museum's "virtual coastline."

Critics initially dismissed such projects as expensive gimmicks, but the educational impact has silenced many skeptics. Studies at the Melbourne Museum showed that visitors who interacted with their Diprotodon (giant prehistoric wombat) AR experience retained 40% more information about Pleistocene extinctions compared to traditional exhibit viewers. More strikingly, emotional engagement metrics spiked—particularly when the holographic creature "noticed" individual visitors and reacted.

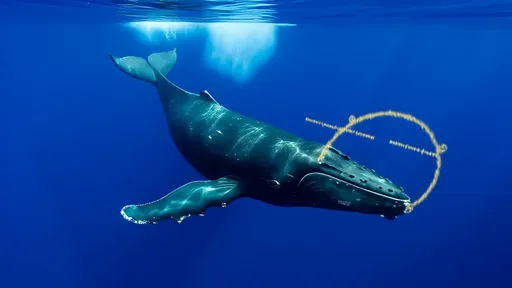

The technology also serves as a sobering mirror for contemporary conservation. Seeing a life-sized Steller's Sea Cow floating beside modern marine mammals highlights how human activity shapes ecosystems. Some institutions intentionally design encounters to provoke unease; at Berlin's Extinction Memorial Hall, visitors must stand motionless to avoid startling a projected Caribbean Monk Seal—a poignant metaphor for how stillness might have prevented its 1952 extinction.

Looking ahead, developers are pushing boundaries with multi-sensory AR. Prototype gloves allow users to "feel" the coarse fur of a digitally reconstructed Irish Elk, while directional sound systems recreate the hypothesized mating calls of Moas (giant flightless birds of New Zealand). The next frontier involves olfactory elements—imagine catching the musky scent of a Saber-toothed Cat's pelt as you virtually examine its teeth.

Ethical debates persist about how these recreations might distort public understanding of extinction's permanence. However, most practitioners position virtual species as educational tools rather than replacements. As Dr. Elena Markov from the Moscow Digital Naturalism Project explains: "We're not pretending these animals exist. We're creating emotional anchors to help people grasp what's been lost—and what could still be saved." In an era of accelerating biodiversity crises, that emotional resonance may prove as valuable as the technology itself.

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025